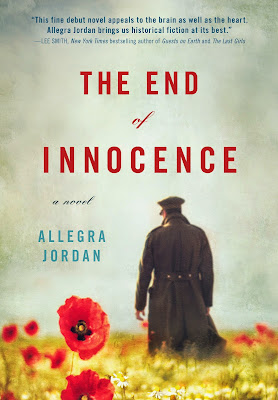

By Allegra Jordan

Sourcebooks Landmark

Historical Fiction

May 1, 2015

ISBN: 9781492609933

$14.99 Trade Paperback

In this enthralling story of love, loss, and divided loyalties, two students fall in love on the eve of WWI and must face a world at war—from opposing sides.

Cambridge, MA, 1914: Helen Windship Brooks, the precocious daughter of the prestigious Boston family, is struggling to find herself at the renowned Harvard-Radcliffe university when carefree British playboy, Riley Spencer, and his brooding German poet-cousin, Wils Brandl, burst into her sheltered world. As Wils quietly helps the beautiful, spirited Helen navigate Harvard, they fall for each other against a backdrop of tyrannical professors, intellectual debates, and secluded boat rides on the Charles River.

But with foreign tensions mounting and the country teetering on the brink of World War I, German-born Wils finds his future at Harvard—and in America—increasingly in danger. When both cousins are called to fight on opposing sides of the same war, Helen must decide if she is ready to fight her own battle for what she loves most.

Based on the true story behind a mysterious and controversial World War I memorial at this world-famous university, The End of Innocence sweeps readers from the elaborate elegance of Boston's high society to Harvard's hallowed halls to Belgium's war-ravaged battlefields, offering a powerful and poignant vision of love and hope in the midst of a violent, broken world.

Amazon | B&N | BAM | IndieBound

Praise for End of Innocence:

"This engaging debut from Jordan tells the love story of two college students who pursue their romance as World War I begins."

"Jordan does a terrific job of contrasting the superficial formalities of the initial chapters depicting New England social life with the grueling realities of life in the trenches. Also on display is her knack for taking what at first seem like throwaway or background details and making them central to the story's last third..."

"A thoughtful look at a turning point in world history.”

Helen is a sympathetic and complicated main character. Her strengths and weaknesses keep the reader's attention, making this a worthwhile read." - Kirkus

"A thoughtful work that offers an interesting perspective on the period." - Booklist

"Reminiscent of Jacqueline Winspear's Maise Dobbs books without the mystery, this novel explores the complications involved when war becomes personal. Jordan builds empathetic characters and an intriguing story. Library Journal " - Library Journal

"Allegra Jordan's The End of Innocence is a moving ode to a lost generation. With lyrical prose and rich historical detail, Jordan weaves a tale in which love overcomes fear, hope overcomes despair, and the indelible human spirit rises up to embrace renewal and reconciliation in the face of loss and destruction." - Allison Pataki, New York Times bestselling author of The Traitor's Wife

"Love in a time of war....surely there is no more compelling or romantic theme in all of literature Yet this fine debut novel appeals to the brain as well as the heart. Allegra Jordan brings us historical fiction at its best." - Lee Smith, New York Times bestselling author of Guests on Earth and The Last Girls

"A delicious, well-crafted historical novel." - Daniel Klein, NYT best-selling co-author of PLATO and A PLATYPUS WALKS INTO A BAR

"Downton Abbey has found a brilliant successor in this spellbinding tale of love, death, and war. The finest war fiction to be published in many years." - Jonathan W. Jordan, bestselling author of Brothers, Rivals, Victors

"An exquisitely beautiful novel." - William Ferris, UNC-Chapel Hill professor and former chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities

Excerpt:

Harvard Yard

Wednesday, August 26, 1914

It was said that heroic architects didn't fare well in Harvard Yard. If you wanted haut monde, move past the Johnston Gate, preferably to New York. The Yard was Boston's: energetic, spare, solid.

The Yard had evolved as a collection of buildings, each with its own oddities, interspersed among large elm trees and tracts of grass. The rich red brickwork of Sever Hall stood apart from the austere gray of University Hall. Appleton Chapel's Romanesque curves differed from the gabled turrets of Weld and the sharp peaks of Matthews. Holworthy, Hollis, and Stoughton were as plain as the Pilgrims. Holden Chapel, decorated with white cherubs above its door and tucked in a corner of the Yard, looked like a young girl's playhouse. The red walls of Harvard and Massachusetts halls, many agreed, could be called honest but not much more. The massive new library had been named for a young man who went down on the Titanic two years before. There were those who would've had the architect trade tickets with the young lad. At least the squat form, dour roofline, and grate of Corinthian columns did indeed look like a library.

The Yard had become not a single building demanding the attention of all around it but the sum of its parts: its many irregular halls filled with many irregular people. Taken together over the course of nearly three hundred years, this endeavor of the Puritans was judged a resounding success by most. In fact, none were inclined to think higher of it than those forced to leave Harvard, such as the bespectacled Wilhelm von Lützow Brandl, a senior and the only son of a Prussian countess, at that hour suddenly called to return to Germany.

A soft rain fell in the Yard that day, but Wils seemed not to notice. His hands were stuffed in his trouser pockets; his gait slowed as the drops dampened his crested jacket, spotted his glasses, and wilted his starched collar. The dying elms, bored to their cores by a plague of leopard moths, provided meager cover.

He looked out to the Yard. Men in shirtsleeves and bowler hats carried old furniture and stacks of secondhand books into their dormitories. This was where the poor students lived. But the place had a motion, an energy. These Americans found no man above them except that he prove it on merit, and no man beneath them except by his own faults. They believed that the son of a fishmonger could match the son of a count and proved it with such regularity that an aristocrat like Wils feared for the future of the wealthy class.

He sighed, looking over the many faces he would never know. Mein Gott. He ran his hands through his short blond hair. I'll miss this.

His mother had just wired demanding his return home. He pulled out the order from his pocket and reread it. She insisted that for his own safety he return home as soon as possible. She argued that Boston had been a hotbed of intolerance for more than three hundred years, and now news had reached Berlin that the American patriots conspired to send the German conductor of the Boston Symphony to a detention camp in the state of Georgia. That city was no place for her son.

She was understandably distressed, although he was certain the reports in Germany made the situation sound worse than it was. The papers there would miss that Harvard was welcoming, for instance. If the front door at Harvard was closed to a student due to his race, class, or nationality, inevitably a side door opened and a friend or professor would haul him back inside by his collar. Once a member of the club, always a member.

But Boston was a different matter. Proud, parochial, and hostile, Boston was a suspicious place filled with suspicious people. It was planned even in pre-Revolutionary times to convey-down to the last missing signpost-"If you don't know where you are in Boston, what business do you have being here?" And they meant it. Wils kept his distance from Boston.

Wils crumpled the note in his hand and stuffed it into his pocket, then walked slowly to his seminar room in Harvard Hall, opened the door, and took an empty seat at the table just as the campus bell tolled.

The room was populated with twenty young men, their books, and a smattering of their sports equipment piled on the floor behind their chairs. After three years together in various clubs, classes, or sports, they were familiar faces. Wils recognized the arrogant mien of Thomas Althorp and the easy confidence of John Eliot, the captain of the football team. Three others were in the Spee Club, a social dining group Wils belonged to. One was a Swede, the other two from England.

The tiny, bespectacled Professor Charles Townsend Copeland walked to the head of the table. He wore a tweed suit and a checked tie and carried a bowler hat in his hand along with his notes. He cast a weary look over them as he placed his notes on the oak lectern.

The lectern was new with an updated crest, something that seemed to give Copeland pause. Wils smiled as he watched his professor ponder it. The crest was carved into the wood and painted in bright gold, different from those now-dulled ones painted on the backs of the black chairs in which they sat. The old crest spoke of reason and revelation: two books turned up, one turned down. The latest version had all three books upturned. Apparently you could-and were expected to-know everything by the time you left Harvard.

It would take some time before the crest found its way into all the classrooms and halls. Yankees were not ones to throw anything out, Wils had learned. He had been told more than once that two presidents and three generals had used this room and the chairs in which they sat. Even without this lore, it still wasn't easy to forget such lineage, as the former occupants had a way of becoming portraits on the walls above, staring down with questioning glares. They were worthy-were you?

Professor Copeland called the class to order with a rap at the podium. "You are in Advanced Composition. If you intend to compose at a beginning or intermediate level, I recommend you leave."

He then ran through the drier details of the class. Wils took few notes, having heard this speech several times before.

"In conclusion," Copeland said, looking up from his notes, "what wasn't explained in the syllabus is a specific point of order with which Harvard has not dealt in some time. This seminar started with thirty-two students. As you see, enrollment is now down to twenty, and the registrar has moved us to a smaller room.

"This reduction is not due to the excellent quality of instruction, which I can assure you is more than you deserve. No. This new war calls our young men to it like moths to the flame. And as we know moths are not meant to live in such impassioned conditions, and we can only hope that the war's fire is extinguished soon.

"If you do remain in this class, and on this continent, I expect you to write with honesty and clarity. Organize your thoughts, avoid the bombastic, and shun things you cannot possibly know.

"Mr. Eliot, I can ward off sleep for only so long when you describe the ocean's tide. Mr. Brandl, you will move me beyond the comfort of tearful frustration if you write yet another essay about something obscure in Plato. Mr. Althorp, your poems last semester sounded like the scrapings of a novice violinist. And Mr. Goodwin, no more discourses on Milton's metaphors. It provokes waves of acid in my stomach that my doctor says I can no longer tolerate."

Wils had now heard the same tirade for three years and the barbs no longer stung. As Copeland rambled, Wils's mind wandered back to the telegram in his pocket. Though a dutiful son, he wanted to argue against his mother's demands, against duty, against, heaven forbid, the philosophy of Kant. His return to Germany would be useless. The situation was not as intolerable as his mother believed. These were his classmates. He had good work to accomplish. The anti-German activity would abate if the war were short-and everyone said it would be.

"Brandl!" Copeland was standing over him.

"Sir?"

"Don't be a toad. Pay attention."

"Yes, sir."

"Come to Hollis 15 after class, Mr. Brandl."

Thomas snickered. "German rat."

Wils cast a cold stare back.

When the Yard's bell tolled the hour, Professor Copeland closed his book and looked up at the class. "Before you go-I know some of you may leave this very day to fight in Europe or to work with the Red Cross. Give me one last word."

His face, stern for the past hour of lecturing, softened. He cleared his throat. "As we have heard before and will hear again, there is loss in this world, and we shall feel it, if not today, then tomorrow, or the week after that. That is the way of things. But there is also something equal to loss that you must not forget. There is an irrepressible renewal of life that we can no more stop than blot out the sun. This is a good and encouraging thought.

"Write me if you go to war and tell me what you see. That's all for today." And with that the class was dismissed.

* * *

Wils opened the heavy green door of Hollis Hall and dutifully walked up four flights of steps to Professor Copeland's suite. He knocked on a door that still bore the arms of King George III. Copeland, his necktie loosened at the collar, opened the door.

"Brandl. Glad I saw you in class. We need to talk."

"Yes, Professor. And I need your advice on something as well."

"Most students do." The professor ushered Wils inside.

The smell of stale ash permeated the room. The clouds cast shadows into the sitting area around the fireplace. Rings on the ceiling above the glass oil lamps testified to Copeland's refusal of electricity for his apartment. The furniture-a worn sofa and chairs-bore the marks of years of students' visits. A pitcher of water and a scotch decanter stood on a low table, an empty glass beside them.

Across the room by the corner windows, Copeland had placed a large desk and two wooden chairs. Copeland walked behind the desk, piled high with news articles, books, and folders, and pointed Wils to a particularly weathered chair in front of him, in which rested a stack of yellowing papers, weighted by a human skull of all things. Copeland had walked by it as if it were a used coffee cup.

"One of ours?" asked Brandl, as he moved the skull and papers respectfully to the desk.

The severe exterior of Copeland's face cracked into a smile. "No. I'm researching Puritans. They kept skulls around. Reminded them to get on with it. Not dawdle. Fleeting life and all."

"Oh yes. ‘Why grin, you hollow skull-'"

"Please keep your Faust to yourself, Wils. But I do need to speak to you on that subject."

"Faust?"

"No, death," said Copeland. His lips tightened as he seemed to be weighing his words carefully. His face lacked any color or warmth now. "Well, more about life before death."

"Mine?" asked Wils.

"No. Maximilian von Steiger's life before his death."

"What the devil? Max...he, he just left for the war. He's dead?"

Copeland leaned toward him across the desk. "Yes, Maximilian von Steiger is dead. And no, he didn't leave. Not in the corporeal sense. All ocean liners bound for Germany have been temporarily held, pending the end of the conflict in Europe."

Wils's eyes met Copeland's. "What do you mean?"

"Steiger was found dead in his room."

"Fever?"

"Noose."

Wils's eyes stung. His lips parted, but no sound came out. "You are sure?"

As Copeland nodded, Wils suddenly felt nauseous, his collar too tight. He had known Max nearly all his life. They lived near each other back in Prussia; they attended the same church and went to the same schools. Their mothers were even good friends. Wils loosened his tie.

"May I have some water, please, Professor?" Wils finally asked in a raspy voice. As Copeland turned his back to him, Wils took a deep breath, pulled out a linen handkerchief, and cleaned the fog from his spectacles.

The professor walked over to a nearby table and poured a glass of water. "How well did you know Max?" he asked, handing the glass to Wils.

He took the tumbler and held it tight, trying to still his shaking hand. "We met at church in Prussia when we were in the nursery. I've known him forever."

"Did you know anything about any gaming debts that he'd incurred?"

Debts? "No."

"Do you think that gaming debts were the cause of his beating last week?" asked Copeland, sitting back in his desk chair.

Wils moved to the edge of his seat. The prügel? Last Wednesday's fight flashed into his mind. There had been a heated argument between Max and a very drunk Arnold Archer after dinner at the Spee dining club. Max had called him a coward for supporting the British but not being willing to fight for them. It wasn't the most sensible thing to do given Archer ran with brawny, patriotic friends. On Thursday at the boathouse Max had received the worst of a fight with Archer's gang.

"It was a schoolboys' fight. They were drunk. Max was beaten because Arnold Archer was mad about the Germans beating the British in Belgium. Archer couldn't fight because America's neutral, so he hit a German who wouldn't renounce his country. These fights break out all the time over politics when too much brandy gets in the way. People get over their arguments."

"Didn't Max make some nationalistic speech at the Spee Club?"

Wils's back stiffened in indignation. "If Max had been British it would have gone unnoticed. But because he was German, Archer beat him." He paused. "Max was going to tell the truth as he knew it, and thugs like Archer weren't going to stop him."

Copeland tapped a pencil against his knee. "How well do you think his strategy worked?"

Wils's eyes widened. "Being beaten wasn't Max's fault, Professor. It was the fault of the person who used his fists."

"Wils, Arnold Archer's father is coming to see me this evening to discuss the case. His son is under suspicion for Max's death."

"I hope Arnold goes to jail."

"Arnold may not have been involved."

Wils set the glass down on the wooden desk and stood up. "He's a pig."

"Wils, according to Arnold, Max tried to send sensitive information about the Charlestown Navy Yard to Germany." A faint tinge of pink briefly colored the professor's cheeks. "Arnold said he knew about this and was going to go to the police. Max may have thought that he would go to jail for endangering the lives of Americans and British citizens. And if what Arnold said was right, then Max may have faced some very serious consequences."

"America's not at war."

The professor didn't respond.

"Why would Max do such a thing then?" asked Wils curtly.

"Arnold says he was blackmailed because of his gaming debts."

"What could Max possibly have found? He's incapable of remembering to brush his hair on most days."

Copeland threw up his hands, nearly tipping over a stack of books on the desk. "I have no idea. Maybe America's building ships for England. Maybe we've captured a German ship. Apparently he found something. Sometime later, Max was found by his maid, hung with a noose fashioned from his own necktie. His room was a wreck." Copeland looked at him intently. "And now the police don't know if it was suicide or murder. Arnold might have wanted to take matters into his own hands-as he did the other night after the Spee Club incident."

Wils ran his hands through his hair. "Arnold a murderer? It just doesn't make sense. It was a schoolboys' fight. And Arnold's a fool, but much more of a village idiot than a schemer."

"Don't underestimate him, Wils. He's not an idiot. He's the son of a very powerful local politician who wants to run for higher office. His father holds City Hall in his pocket."

"Are you speaking of Boston City Hall?"

"Yes."

"I could care less about some martinet from Boston. I'm related to half the monarchs in Europe." Wils sneered.

"City Hall has more power over you right now than some king in a faraway land," said Copeland. "Arresting another German, maybe stopping a German spy ring-that would be exactly the thing that could get a man like Charles Archer elected to Congress. I'd recommend you cooperate with City Hall on any investigation into Max's death. If you have information, you will need to share it."

"If Arnold killed Max-" He stopped, barely able to breathe. Max dead by Arnold's hand? Unthinkable. "Was there a note?"

"No, nothing. That's why the Boston police may arrest Archer even if his father does run City Hall. Either it was a suicide and it won't happen again, or perhaps we need to warn our German students about...a problem." Copeland's fingers brushed the edge of his desk. "That was the point of my summoning you here now. It could've been suicide. Therefore, the police want to talk with you before innocent people are accused, and I'd recommend you do it."

But Wils had already taken the bait. "Innocent people? Arnold Archer? Is this a joke?" asked Wils.

"He may not be guilty."

Wils paused. "I'm not sure how much money his father's giving Harvard, but it had better be a lot."

"That's most uncharitable!"

"And so is the possible murder of a decent human! Where's Professor Francke? I'd like to speak with him. He is a great German leader here on campus whom everyone respects. He'll know how to advise me."

"You are right. Professor Francke is a moderate, respected voice of reason. But he's German and the police questioned him this morning. He is cooperating. His ties to the kaiser have naturally brought him under suspicion. City Hall thinks he could be a ringleader of a band of German spies. The dean of students asked me to speak with you and a few others prior to your discussions with the police. They should contact you shortly regarding this unpleasantness."

"If that is all-" Wils bowed his head to leave, anger rising in his throat from the injustice of what he'd heard. First murder and now harassment were being committed against his countrymen, and somehow they were to blame for it? Not possible. Professor Francke was one of the most generous and beloved professors at Harvard. Max was a harmless soul.

"Wils, you had said you wished to ask me about something."

Wils thought back to his mother's telegram. Perhaps she'd been right to demand his return after all. He looked up at Copeland, sitting under an image of an old Spanish peasant. He seemed to have shrunk in his large desk chair.

"No, Professor. Nothing at all. Good day."

Copeland didn't rise as Wils turned to enter the dimly lit hallway. As his eyes adjusted, a famous poem Copeland had taught him in class-Matthew Arnold's "Dover Beach"-came to him. Wils turned back to his teacher and said:

"For the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain-"

Copeland brightened. "‘Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, where ignorant armies clash by night,'" they finished together. Wils nodded, unable to speak further.

"Matthew Arnold has his moments. Do take care, Wils. Stay alert. I am concerned about you and want you to be safe. The world is becoming darker just now. Your intellectual light is one worth preserving. Now please close the door from the outside." Copeland looked down again, and the interview was over.

* * *

The rain had driven the students inside their dormitories and flooded the walkways in Harvard Yard. As Wils left Hollis Hall, he removed his tie and pushed it into his pocket. The damned Americans talk brotherhood, he thought, but if you're from the wrong side of Europe you're no brother to them.

Max dead. Arnold Archer under suspicion. And what was all of that ridiculous nonsense about the Charlestown Navy Yard, he wondered, deep in thought, nearly walking into a large blue mailbox. He crossed the busy street and walked toward his room in Beck Hall.

In his mind, he saw Max trading barbs at the dinner table and laughing at the jests of Wils's roommate, Riley, an inveterate prankster. And how happy Max had been when Felicity, his girlfriend from Radcliffe College, had agreed to go with him to a dance. But he'd been utterly heartbroken when she deserted him last year for a senior. This past summer Wils and Max had walked along the banks of the Baltic, when they were back in Europe for summer vacation. He said he would never get over her and he never really had. So what had happened to him?

Anger at the injustice of Max's death welled up inside Wils as he opened the arched door of Beck Hall and walked quickly past Mr. Burton's desk. The housemaster didn't look up from his reading. Wils shut the door to his room behind him. His breath was short. His hands hadn't stopped trembling. He had to find Riley and discuss what to do about Arnold.

What was happening to his world? His beautiful, carefully built world was cracking. Germany and Britain at war? Max dead? Professor Francke hauled in and questioned?

Wils felt a strange fury welling up inside of him. He wanted something to hurt as badly as he did. He picked up a porcelain vase and hurled it against the brick fireplace. It crashed and shattered, the blue-and-white shards scattering over the crimson rug.

About the Author:

Allegra Jordan is a writer and global innovation consultant. A graduate with honors of Harvard Business School, she led marketing at USAToday.com for four years and has taught innovation in sixteen countries and five continents.

3 signed copies of End of Innocence

Open 5/14 - 6/1

Third-Party Giveaway

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Leave me a comment! I love to talk books :)